A recent study has revealed a potential connection between brain damage and the emergence of criminal behavior. Specifically, the research highlights the disruption of the uncinate fasciculus pathway, a crucial neural link. The findings suggest that damage to this area, which connects regions governing emotion and decision-making, correlates with an increased likelihood of criminal activity, raising profound ethical questions about culpability and legal responsibility in cases involving brain injury.

Could alterations in the brain truly transform a law-abiding individual into a criminal? A groundbreaking study suggests this might be possible, indicating that damage to a specific brain region may significantly contribute to criminal or violent behavior.

Researchers from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School have shed light on the neurological underpinnings of violence and moral decision-making. Their findings were published in Molecular Psychiatry.

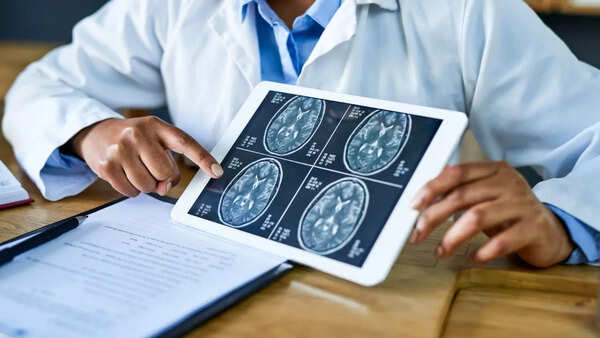

To investigate the relationship between brain injury and criminal behavior, researchers examined brain scans of individuals who began committing crimes after experiencing brain injuries from various causes such as strokes, tumors, or traumatic events.

These scans were compared to those of 706 individuals exhibiting other neurological symptoms, including memory loss and depression. The results were compelling. The study revealed that damage to a specific brain pathway on the right side, known as the uncinate fasciculus, was a common factor among those who exhibited criminal behavior. This pattern was also observed in individuals who committed violent crimes.

"This part of the brain, the uncinate fasciculus, is a white matter pathway that acts as a cable connecting regions responsible for emotion and decision-making. When this connection is disrupted on the right side, a person's ability to regulate emotions and make moral choices can be severely impaired," explained Christopher M. Filley, MD, professor emeritus of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a co-author of the study.

Isaiah Kletenik, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and lead author of the study, added, "While it's well-established that brain injury can lead to problems with memory or motor function, the brain's role in guiding social behaviors like criminality is more controversial. This raises complex questions about culpability and free will."

Kletenik shared that his experience evaluating patients who began committing violent acts following the onset of brain tumors or degenerative diseases during his behavioral neurology training at the University of Colorado School of Medicine sparked his interest in the brain basis of moral decision-making.

To further validate their findings, the researchers conducted a comprehensive connectome analysis, which involved using a detailed map of how different brain regions are interconnected. The analysis confirmed that the right uncinate fasciculus was the neural pathway most consistently linked to criminal behavior.

Filley emphasized, "It wasn't just any brain damage; it was damage specifically in the location of this pathway. Our findings suggest that this specific connection may play a unique role in regulating behavior."

The specific pathway connects brain regions involved in reward-based decision-making with those that process emotions. Damage to this link, particularly on the right side, can lead to difficulties in controlling impulses, anticipating consequences, or feeling empathy, all of which can contribute to harmful or criminal actions.

The researchers also noted that not everyone with this type of brain injury becomes violent. However, damage to this tract may contribute to the new onset of criminal behavior following an injury.

"This work could have real-world implications for both medicine and the law. Doctors may be better equipped to identify at-risk patients and provide effective early interventions. Furthermore, courts might need to consider brain damage when assessing criminal responsibility," Filley added.

Kletenik also emphasized the crucial ethical questions raised by the study's findings. "Should brain injury factor into how we judge criminal behavior? Causality in science is not defined in the same way as culpability in the eyes of the law. Still, our findings provide valuable data that can help inform this discussion and contribute to our growing knowledge of how social behavior is mediated by the brain."

Newer articles

Older articles

Android Security Alert: Government Warns of Critical Flaws Exposing User Data

Android Security Alert: Government Warns of Critical Flaws Exposing User Data

Bezos-Backed Methane-Tracking Satellite Mission Ends Prematurely After Loss of Contact

Bezos-Backed Methane-Tracking Satellite Mission Ends Prematurely After Loss of Contact

Sanjog Gupta Named ICC's New Chief Executive Officer, Set to Lead Cricket's Global Expansion

Sanjog Gupta Named ICC's New Chief Executive Officer, Set to Lead Cricket's Global Expansion

Greg Chappell: Rishabh Pant is Revolutionizing Cricket with Unorthodox Batting

Greg Chappell: Rishabh Pant is Revolutionizing Cricket with Unorthodox Batting

Heart Attack Warning: 5 Subtle Signs to Watch for a Month Prior

Heart Attack Warning: 5 Subtle Signs to Watch for a Month Prior

Staying Hydrated May Significantly Lower Risk of Heart Failure, New Study Finds

Staying Hydrated May Significantly Lower Risk of Heart Failure, New Study Finds

Asia Cup 2025: ACC Eyes September Start Date Amid Growing Optimism

Asia Cup 2025: ACC Eyes September Start Date Amid Growing Optimism

FIFA Club World Cup 2025: Upsets, Messi Magic, and Weather Woes Define Group Stage

FIFA Club World Cup 2025: Upsets, Messi Magic, and Weather Woes Define Group Stage

Gavaskar Calls for Kuldeep Yadav's Inclusion in Second Test Amid Bumrah Fitness Concerns, Eyes Batting Reshuffle

Gavaskar Calls for Kuldeep Yadav's Inclusion in Second Test Amid Bumrah Fitness Concerns, Eyes Batting Reshuffle

Doctor Reacts to Rishabh Pant's Somersault After Century: 'Unnecessary!' – Surgeon Who Aided Recovery Speaks Out

Doctor Reacts to Rishabh Pant's Somersault After Century: 'Unnecessary!' – Surgeon Who Aided Recovery Speaks Out